|

|

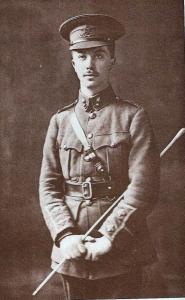

| Captain Wilfred Dryden PRITCHARD | |

|

8th Battery, 13th Brigade, Royal Field Artillery Date of birth: 6th December 1890 Date of death: 25th September 1915 Killed in action aged 24 Commemorated on the Loos Memorial Panel 3 |

|

| Wilfred Dryden Pritchard was born at Mandalay in Burma on the 6th of December 1890 the eldest son of Major Alfred Bassett Pritchard, Indian Army, and Louisa Isabella (nee Dryden) Pritchard of Canon’s Ashby, Woodford Halse, Rugby in Warwickshire. He was educated at Temple Grove School and at Lancing College where he won an Exhibition and was in Olds House from September 1904 to December 1908. He was appointed as a House Captain in 1908, was in the Football XI from 1906 to 1908 and was a member of the Officer Training Corps from September 1904 to December 1908 where he rose to the rank of Sergeant. He applied for entrance to the Royal Military Academy Woolwich on the 27th of March 1909 and, on leaving, was commissioned as a 2nd Lieutenant in the Royal Artillery on the 23rd of December 1910. Shortly after being commissioned he was posted to India where he served until coming home in August 1914. He was wounded on the 11th of November 1914 and his father received the following telegram dated the 13th of November 1914:- "Regret to inform you that Lieut. W.D. Pritchard RFA was slightly wounded on 11 November. No further details received." On his return to the front he served as an Forward Observation Officer attached to the Black Watch. In a letter dated the 12th of March 1915 he wrote home describing the British attack two days earlier at Neuve Chappelle:- "I have seen our men make four charges and very gallant sights they were; also I have seen poor fellows with arms and legs shot away dying in agony, and the smell of blood was everywhere. Trenches and houses were full of men so that nearly every shell was bound to take effect. What happened was that at 7am three days ago all the guns we have got concentrated here (and we have a tremendous number), opened fire. At the end of half an hour we all raised our range and the infantry charged, four regiments in line. They hardly suffered at all from artillery but some machine guns in a flank trench, which had not been properly shelled, enfiladed the advancing line. We took their trench for some 1,000 yards but our right regiment had to come back bringing some prisoners. Further to our left another brigade had advanced but two attacks diverged slightly and left a piece of German trench about 300 yards long in their hands. However we came down it from each side and the right hand regiment charged again and when our men got within 30 yards of the trench the Germans (200) held up their hands. They were brought straight back to where I was across the open with shells and bullets whistling about but we all jumped up awfully pleased and cheered our men. We pushed on some 500 yards beyond their fire trench and some of the men farther still. We could not go further than that as on our right (we being the right of the attack) the Germans still held their trenches. On our left, we had taken the village but beyond that again the Division there had not advanced far enough, although beyond that again there had been an advance of some 1,000 yards. In the gap left the Germans were strongly entrenched with machine guns so that the right of my Division's attack could not get on because of it being the right and pivot of the whole attack and the left could not because it was advancing into a V in which it could be enfiladed on both sides. The next day my division held their ground hoping for the centre to come up but the Division still more to the left made some ground although the centre did not. This day I did not observe. On the third day I was observing again, being down there all that night, trying to get telephone wire out to a house in the captured village which I succeeded in doing. At 5 in the morning, a heavy shelling was started by the Germans and I came rushing back to the old observing house to find that the Germans had counterattacked on the trench just under the observing house and the extreme original left trench (ie. the pivot trench) of our attack. The most part of the attackers were driven back; a good many were killed and about 70 got within 30 yards of the trench and were lying down. Our men started bombing them with hand bombs. Suddenly five got up and were shot down. Then the remainder threw down their rifles and put up their hands and our men fetched them in with the German rifles going all the time. We then saw our advanced right having a bomb throwing contest with the Germans in the same trench as they were. All of a sudden we spotted a party of Germans sapping out from their trench towards our advanced right and about 30 yards from it. One could see their pickelhaubers . The trouble was how to reach them without hitting our own men. Unfortunately my telephone wire was broken; however I sent down a message by the wire of one of the other batteries of the Brigade. Also a field howitzer took them on and dropped the third shell right into them. Meanwhile we had told our infantry in the extreme original trench (who could not see them until they got up owing to being so low down). When the big shells started dropping on them, they tried to crawl back but our shrapnel and the infantry's bullets got anyone who showed himself and then to our intense delight that German shells started dropping on them. Not more than two or three of the 30 or so original ones got away. I had pot shots at them with a rifle from the observing house as I could not get through to the battery. We did two bombardments of the enemy's new line to try to help our chaps to push on but our reentrant centre stopped an advance! However, a lot of the Germans started to crawl away from their extreme right point of the trench they held in front of my brigade and we killed quite a few of them there. Another counter attack they made away to the left lost its way in the mist and wandering up towards our trenches was wiped out, so some people say, to the extent of 400 men. We found ourselves held up now by a strong line with machine guns and have advanced 1,500 yards at the best and 300 at the worst places over a front of 4,000 yards. We lost pretty heavily in places from shell fire and from machine guns. We are now expecting a counter attack and our men are entrenching hard in the positions we have won. The infantry of my Division did very well. They are a jolly fine lot of chaps. The native regiments did very well indeed, but the British and Scotch (especially the Scotch) regiments are simply grand fellows! The Germans we captured are chiefly young fellows, some of them good stuff, but mostly evidently civilians half trained into soldiers. We are going back into rest tomorrow I believe, and I am sure, the infantry deserve it. I shall not be sorry myself. I got a helmet, a cap, a bayonet, a very nice camera, with a film of three photos on it given me by a prisoner and a pocket flash lamp as trophies. We lost heavily but I think they lost more. After the Germans had put up their hands our men came up to them. A German officer pulled out his revolver and shot Gilroy of the Black Watch in the stomach. He is dangerously wounded (this was Lieutenant Kenneth Reid Gilroy 2nd Battalion Black Watch who died of his wounds on the 12th of March 1915). They made him dig his own grave and shot him into it. Shooting was too good for him. Our men bear no malice to the Germans. Time and again I have seen men go out in daylight under heavy fire to bring in German wounded lying in front of our trenches. One German gave the Sergeant who did this for him, his gold watch and chain. The German prisoners looked quite glad to be captured, but rather dazed by the awful bombardment they got." On the morning of the 25th of September 1915, the opening day of the Battle of Loos, Wilfred Pritchard was serving as Forward Observation Officer attached to the 1/4th Battalion Black Watch. He was to go forward with them in order to maintain communication with, and to direct the fire of, his Battery in the rear. At 5.50am the British artillery barrage began falling on the enemy trenches opposite and, ten minutes later, the men of the Black Watch poured out of their trenches and into no man's land. As soon as they rose from their trenches they were met with enemy rifle fire which increased in intensity as the advance progressed. As they crossed the open space the rifle fire was joined by shrapnel fire from the enemy artillery which took a heavy toll of the assaulting troops. In spite of this the depleted Highlanders carried the first German line and swept on towards the second objective, the Moulin de Pietre, where they drove the enemy from the surrounding trenches and began to consolidate these positions. Casualties for the attack had been very heavy and the battalion found itself in advance of the battalions on either side, leaving their flanks badly exposed. At the same time, all communication with the rear had been lost and runners who were sent back did not get through the heavy enemy artillery fire which was falling on no man's land and the old British front line. By 11am enemy bombers were working their way around the Scot's flanks. gradually the Highlanders were forced back, position by position until eventually they were forced to return to the line they had started from having lost around half their number. Wilfred Pritchard was last heard of at noon when he telephoned his Battery from a cottage to direct their fire against the German counterattack. His father received the following telegram dated the 29th of September 1915:- "Regret to inform you that Capt. W.D. Pritchard R. Field Artillery is reported missing. Any further news will be telegraphed as soon as received." His Commanding Officer wrote:- "I cannot express how sad we all are about it. We all liked him so much. He was a first rate man and officer." His former Commanding Officer wrote:- "I was very sorry to hear of the death of Rutherford and of your boy. Any commanding officer might be proud to have such subalterns. When the war is over I propose giving a small piece of plate to the 14th Battery as a memento of them---both good friends and gallant gentlemen." A brother officer wrote:-" "He was one of the bravest and dearest little chaps that ever was. When I heard he was missing I can't tell you how I felt. You ought to be proud of him. He was just one of the very best, a white man to the very core, and as long as I live I shall be proud to have known him." On the 13th of April 1916 a report was received from Berlin stating that Wilfred Pritchard had "fallen and buried" although no place of burial was recorded. His brother, Rifleman Lawrence Dryden Prichard OL 1/5th (City of London) Battalion (London Rifle Brigade), was killed in action on the 28th of August 1918. He is commemorated on a tablet in the parish church at Canon’s Ashby in Northamptonshire. |

|

| |

| Olds House |

Back